Update: This fund has been liquidated.

Objective

The fund seeks long-term growth by investing in global corporations involved in infrastructure and utility projects. The fund holds about 100 stocks, 70% of its investments (as of 3/31/11) are outside of the U.S and 20% are in emerging markets. The manager expects about 33% of the portfolio to be invested in emerging markets. The portfolio is dominated by utilities (45% of assets) and industrials (40%). Price highlights the fund’s “substantial volatility” and recommends it as a complement to a more-diversified international fund.

Adviser

T. Rowe Price. Price was founded in 1937 and now oversees about a half trillion dollars in assets. They advise nearly 110 U.S. funds in addition to European funds, separate accounts, money markets and so on. Their corporate culture is famously stable (managers average 13 years with the same fund), collective and risk conscious. That’s generally good, though there’s been some evidence of groupthink in past portfolio decisions. On whole, Morningstar rates the primarily-domestic funds higher as a group than it rates the primarily-international ones.

Managers

Susanta Mazumdar. Mr. Mazumdar joined Price in 2006. He was, before that, recognized as one of India’s best energy analysts. He earned a Bachelor of Technology in Petroleum Engineering and an M.B.A., both from the Indian Institute of Technology.

Management’s Stake in the Fund

None. Since he’s not resident in the U.S., it would be hard for him to invest in the fund. Ed Giltanen, a TRP representative, reports (7/20/11) that “we are currently exploring issues related to his ability to invest” in his fund. Only one of the fund’s directors (Theo Rodgers, president of A&R Development Corporation) has invested in the fund. There are two ways of looking at that pattern: (1) with 129 portfolios to oversee, it’s entirely understandable that the vast majority of funds would have no director investment or (2) one doesn’t actually oversee 129 funds, one nods in amazement at them.

Opening date

January 27, 2010.

Minimum investment

$2,500 for all accounts.

Expense ratio

1.10%, after waivers, on assets of $50 million (as of 5/31/2011). There’s also a 2% redemption fee on shares held fewer than 90 days.

Comments

Infrastructure investing has long been the domain of governments and private partnerships. It’s proven almost irresistibly alluring, as well as repeatedly disappointing. In the past five years, the vogue for global infrastructure investing has reached the mutual fund domain with the launch of a dozen funds and several ETFs. In 2010, T. Rowe Price launched their entrant. Understanding the case for investing there requires us to consider four questions.

What do folks mean by “infrastructure investing”? “Infrastructure” is all the stuff essential to a country’s operation, including energy, water, and transportation. Standard and Poor’s, which calculates the returns on the UBS World Infrastructure and Utilities Index, tracks ten sub-sectors including airports, seaports, railroads, communications (cell phone towers), toll roads, water purification, power generation, power distribution (including pipelines) and various “integrated” and “regulated” categories.

Why consider infrastructure investing? Those interested in the field claim that the world has two types of countries. The emerging economies constitute one type. They are in the process of spending hundreds of billions to create national infrastructures as a way of accommodating a growing middle class, urbanization and the need to become economically competitive (factories without reliable electric supplies and functioning transportation systems are doomed). Developed economies are the other class. They face the imminent need to spend trillions to replace neglected, deteriorating infrastructure that’s often a century old (a 2009 engineering report gave the US a grade of “D” in 15 different infrastructure categories). CIBC World Markets estimates there will be about $35 trillion in global infrastructure investing over the next 20 years.

Infrastructure firms have a series of unique characteristics that makes them attractive to investors.

- They are generally monopolies: a city tends to have one water company, one seaport, one electric grid and so on.

- They are in industries with high barriers to entry: the skills necessary to construct a 1500 mile pipeline are specialized, and not easily acquired by new entrants into the field.

- They tend to enjoy sustained and rising cash flows: the revenues earned by a pipeline, for example, don’t depend on the price of the commodity flowing through the pipeline. They’re set by contract, often established by government and generally indexed to inflation. That’s complemented by inelasticity of demand. Simply put, the rising price of water does not tend to much diminish our need to consume it.

These are many of the characteristics that made tobacco companies such irresistible investments over the years.

While the US continues to defer much of its necessary infrastructure investment, demand globally has produced startling results among infrastructure stocks. The key index, UBS Global Infrastructure and Utilities, was launched in 2006 with backdated results from 1990. It’s important to be skeptical of any backdated or back-tested model, since it’s easy to construct a model today that would have made scads of money yesterday. Assuming that the UBS model – constructed by Standard and Poor’s – is even modestly representative, the sector’s 10-year returns are striking:

| UBS World Infrastructure and Utilities | 8.6% |

| UBS World Infrastructure | 11.1 |

| UBS World Utilities | 8.4 |

| UBS Emerging Infrastructure and Utilities | 16.5 |

| Global government bonds | 7.0 |

| Global equities | 1.1 |

| All returns are for the 10 years through March 2010 | |

Now we get to the tricky part. Do you need a dedicated infrastructure fund in your portfolio? No, it’s probably not essential. A complex simulation by Ibbotson Associates concluded that you might want to devote a few percent of your portfolio to infrastructure stocks (no more than 6%) but that such stocks will improve your risk/return profile by only a tiny bit. That’s in part true because, if you have an internationally diversified portfolio, you already own a lot of infrastructure stocks. TRGFX’s top holding, the French infrastructure firm Vinci, is held by not one but three separate Vanguard index funds: Total International, European Stock and Developed Markets. It also appears in the portfolios of many major, actively managed international and diversified funds (Artisan International, Fidelity Diversified International, Mutual Discovery, Causeway international Value, CREF Stock). As a result, you likely own it already.

A cautionary note on the Ibbotson study cited above: Ibbotson says you need marginal added exposure to infrastructure. The limitation of the Ibbotson study is that it assumed that your portfolio already contained a perfect balance of 10 different asset classes, with infrastructure being the 11th. If your portfolio doesn’t match that model, the effects of including infrastructure exposure will likely be different for you.

Finally, if you did want an infrastructure fund, do you want the Price fund? Tough question. The advantages of the Price fund are substantial, and flow from firmwide commitments: expect below average expenses, a high degree of risk consciousness, moderate turnover, management stability, and strong corporate oversight. That said, the limitations of the Price fund are also substantial:

Price has not produced consistent excellence in their international funds: almost all of them are best described with words like “solid, consistent, reliable, workman-like.” While several specialized funds (Africa and Middle East, for example) appear strikingly weak, part of that comes from Morningstar’s need to place very specialized funds into their broad emerging markets category. The fact that the Africa fund sucks relative to broadly diversified emerging markets funds doesn’t tell us anything about how the Africa fund functions against an African benchmark. Only one of the Price international funds (Global Stock) has been really bad of late (top 10% of its peer group over the three years ending 7/22/11), and even that fund was a star performer for years.

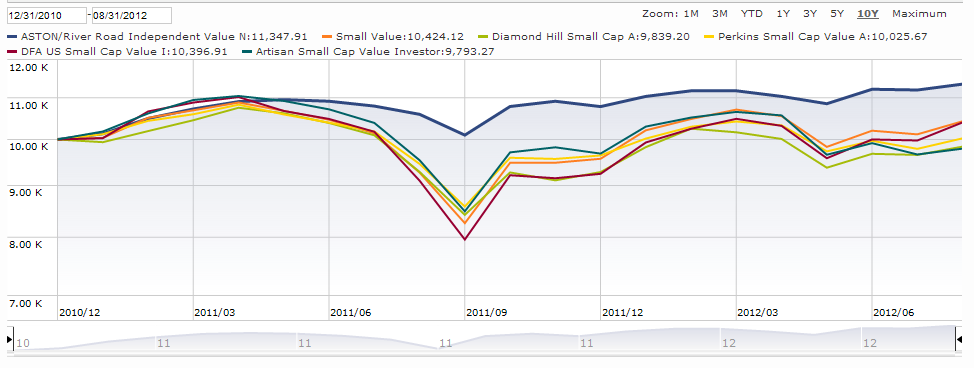

Mr. Mazumdar has not proven himself as a manager: this is his first stint as a manager, though he has been on the teams supporting several other funds. To date, his performance has been undistinguished. Since inception, the fund substantially trails its broad “world stock” peer group. That might be excused as a simple reflection of weakness in its sector. Unfortunately, it also trails almost everyone in its sector: for both 2011 (through late July) and for the trailing 12 months, TRGFX has the weakest performance of any of the twelve mutual funds, CEFs and ETFs available to retail investors. The same is true of the fund’s performance since inception. It’s a short period and his holdings tend to be smaller companies than his peers, but the evidence of superior decision-making has not yet appeared.

The manager proposes a series of incompletely-explained changes to the fund’s approach, and hence to its portfolio. While I have not spoken with Mr. Mazumdar, his published work suggests that he wants to move the portfolio to one-third North America, one-third Europe and one-third emerging markets. That substantially underweights North America (50% of global market cap) while hugely overweighting the emerging markets (11%) and ignoring developed markets such as Japan. The move might be brilliant, but is certainly unexplained. Likewise, he professes a plan to shift emphasis from the steadier utility sector toward the more dynamic (i.e., volatile) infrastructure sector without quite explaining why he’s seeking to rebalance the fund.

Bottom Line

The case for a dedicated infrastructure fund, and this fund in particular, is still unproven. None of the retail funds has performed brilliantly in comparison to the broad set of global funds, and none has a long track record. That said, it’s clear this is a dynamic sector that’s going to draw trillions in cash. If you’re predisposed to establish a small position there as a test, TRGFX offers a sensible, low cost, highly professional choice. To the extent it reflects Price’s general international record, expect performance somewhat on par with an index fund’s.

Fund website

T. Rowe Price Global Infrastructure. For those with a finance degree and a masochistic streak (or an abnormal delight in statistics, which is about the same thing), Ibbotson’s analysis of the portfolio-level effects of adding infrastructure investments is available as Infrastructure and Strategic Asset Allocation, 2009.

© Mutual Fund Observer, 2011. All rights reserved. The information here reflects publicly available information current at the time of publication. For reprint/e-rights contact David@MutualFundObserver.com.